Is Leverage Actually Bad?

Surprisingly, No

TL;DR

Leverage, going into debt, is not the devil conventional wisdom makes it out to be, in fact it is extremely common and accepted – in real estate.

Used judiciously to buy equities (stocks), leverage can enable an investor to avoid concentrating their meaningful compounding on an asset or two (as is the case with real estate) and just a decade or so (as is the case if you simply invest cash savings in the S&P 500).

Dividend growth stocks seem like perfect targets to buy with debt, as they are usually reliable businesses, and their yields (with tax-deductions for Canadians) can cover the interest payments, while the investor keeps the compounding of the share price and the growth of the dividend.

Acknowledging the typical risks of borrowing, buying dividend growth stocks on leverage is rationally sensible but behaviourally fraught. I don’t know anyone who does so and would be taking a large “look stupid in the eyes of my family and peers” risk, which is relevant, if I’m being honest.

Canadians can look up the “Smith Manoeuvre” if this sounds interesting.

As usual, here’s the reminder I’m not a financial expert, just posting my learning process for others to critique and perhaps benefit from.

This topic, even more than most, is highly personal so don’t go out and do anything I discuss.

Introduction:

There’s an underappreciated risk involved with saving for retirement.

As young people we don’t often have much left over to invest, while as older people we likely will. This means that early in our lives we get little exposure to the compounding effect of markets, and later get a lot of exposure. As a result, the average saver is unwittingly timing the market, and timing the market is luck-based.

To elaborate slightly, even if we compound at high rates early on, the actual sum invested is likely small enough to not make a huge difference. Whereas as older people with more to invest, even with a lower rate of return, the actual dollar value of the investment gains will be meaningful. In a sense, our biggest investment gains/losses will be “time concentrated” towards the latter stages.

This isn’t a bad thing if the latter stages do great, but what if they don’t? There’s a timing risk here; it would be better to diversify across time our meaningful market exposure, if possible.

Claiming to mitigate this risk is a concept called “Lifecycle Investing” that recommends leverage, borrowing to invest, while young and to slowly de-lever as one ages. Essentially, borrow to invest while young to get meaningful exposure to markets at all stages of life, to diversify investments across time periods.

Imagine reaching a critical mass of savings right when the market goes sideways for a decade, not ideal. As such, it makes sense to try to have meaningful sums invested over as many time periods as possible to avoid the risk of concentrating one’s best potential compounding years into “lost decades.” That’s a risk, they argue, that leverage can ameliorate.

The academic paper is here, they have a book too, and there is lots of discussion about it online.

Feelings Towards Borrowing to Invest

There’s a financial advisor truism that “diversification if the only free lunch in investing” so it makes intuitive sense that using leverage to add diversification of time, in addition to number of investments, would reduce risk and lead to more consistent positive outcomes.

It doesn’t feel good though, borrowing against your house, buying stocks on margin, or treading into options. Personally, if I want to get ahead on retirement saving, I feel better forgoing some diversification and concentrating into equities I think have a high probability of beating the S&P 500. By not borrowing, I can’t lose more than I invest, I avoid the possibility of a total wipe-out.

The authors of “Lifecycle Investing” argue that even if a total wipe-out does happen, if you’re young enough, you have time to make it up and then some. Additionally, they argue that this is only a possibility, not a probability, with a little knowledge.

These suggestions make me squeamish as they go against a lot of the prevailing financial wisdom that leverage, borrowing to invest, is to be avoided.

Until we consider real estate. What the authors describe, levering up early and slowly de-levering over time, is precisely what a mortgage is. With a mortgage you put down a little money, borrow a lot, and over time pay it back until you eventually are debt-free, usually when you’re a lot older, provided you don’t default in the meantime.

Some people, once they’ve built up enough equity in their home, even borrow against their existing home to buy another one with 5-10x leverage – and this is a common-sense good idea, “winning” for young people. The mortgage is a perfect example of lifecycle investing, diversifying one’s time of meaningful market exposure.

To do this though, mortgages and investment properties sacrifice diversification of assets for diversification of time. A person who borrows against the equity in their home to purchase an investment property may gain meaningful exposure to markets across all stages of their life but concentrates it into a single property in a single asset class. The real estate investor has improved their diversification of time but has done so by concentrating their assets. Have they improved their risk profile?

The ideal retirement savings strategy would allow for diversification of time and assets; borrowing to buy equities (stocks) while young might be the best risk-adjusted retirement savings plan.

How would it work?

Note: There is some Canadian bias here, as I am one and we have certain tax laws that make a certain strategy more appealing, but I think the principle that judicious use of leverage while young is beneficial can still be generalized. Nonetheless, non-Canadians won’t gain as much from this section as Canadians.

In Canada, if you take out a loan to invest in income-producing assets, like rental properties or dividend stocks, the interest you pay on the loan is tax-deductible, meaning you can use that interest expense to lower your taxable income, resulting in less taxes paid (in the same way as RRSP contributions).

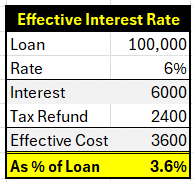

For example, borrow $100,000 (probably against your home equity) at 6%. You’ll pay $6000 of interest that year. Invest that $100,000 in dividend stocks yielding 5%, and you’ll receive $5000. So, you pay $6,000 in interest and get $5,000 in cash dividends. You’ve lost $1,000 in cash flow, right?

No, in fact, because the loan went towards income-producing assets (dividend stocks), the interest you paid ($6,000) can be used to reduce your income by $6,000; a $100,000 income becomes $94,000 for tax purposes ($100,000 - $6,000).

This is significant because if you pay 40% income tax, instead of having to pay $40,000 in taxes ($100,000 x 40%) you pay $37,600 ($94,000 x 40%), meaning you will get a tax refund of $2,400 ($40,000 - $37,600). That $2,400 refund covers your $1,000 cash flow deficit, and then some.

So, over the course of the year, you pay $6,000 in interest, but get $2,400 of it back at tax time, resulting in a net cost of borrowing of $3,600 ($6,000 - $2,400) for the year. Your loan was for $100,000 meaning the effective interest rate is not the stated 6%, but, because of the tax effect, 3.6% instead ($3,600 / $100,000).

If you think of the interest cost as $3,600 (due to the tax refund), the result of that year is net positive cash flow of $1,400 ($-3,600 interest + $5,000 dividends). That positive “spread” can go towards more stocks or home equity; the snowball begins.

And this is all before growth in the stock. Stocks, especially dividend growth stocks, reliably go up over time, which, barring calamitous economic events, you’re getting for “free.” Moreover, because these are stocks that grow their dividend, that $5,000 yield in the first year will increase each year thereafter: the snowball gains momentum.

Here’s how that looks visually:

Notice how the value of the stocks steadily outpaces that of the loan (assuming nothing crazy positive or negative happens).

Because the dividend payouts grow each year (dividend growth stocks), the yield on the original $100,000 increases steadily and so does the excess cash coming in (assuming interest rates don’t go dramatically higher or lower from the original rate).

Here’s the data in table form for the junkies out there:

Assuming 5% annual growth in share price, 5% annual growth in dividend, and average interest rate of 6% on a $100,000 loan, this investor would exit Year 10 having collected $22,889 of positive cash flow and with a $55,133 capital gain, for a total of $78,022 made with someone else’s money, not bad at all.

Considering the stocks we’re dealing with are the likes of regulated utility companies and government protected oligopolies, these assumptions are not too wild over long enough time frames.

The point is the math seems to check out.

Risks and Perspectives

This can sound too good to be true, but this is exactly how people make money in real estate. For example, we may know someone who has borrowed money to buy a rental property. The idea is usually that the tenants pay the mortgage while the owner compounds the equity and collects any excess cash flow. The idea of using debt to buy dividend growth stocks is like investing in a rental property, except instead of tenants “paying the mortgage,” stocks do.

Of course, this is leverage, there are risks. Mainly that interest rates go up, stock values go down, and dividends get cut, which are understandably frightening. These are the exact risks everyone who has ever bought a house with a mortgage take, however. Take on debt and anything that causes you to be unable or unwilling to pay it, like a sharp rise in interest rates, job loss, and/or sudden loss in equity value, means you lose your house.

Notably, instead of 5-10x debt to equity as is customary with real estate (aka 10-20% down), with dividend stocks you can lever just 1.5x to 2x and, because equities have historically outperformed real estate, you don’t need huge multiples of debt (leverage) to get similar wealth-creation.

Additionally, instead of owning one asset, as is the case with a rental property, the levered dividend investor can easily diversify into 40-50 uncorrelated stocks, reducing the risk of something totally unpredictable being ruinous.

Moreover, the leverage is more easily reversed if required, because stocks can be bought and sold quickly and easily (liquid), while real estate is a pain to sell and takes time (illiquid), not to mention the headaches of maintenance and dealing with people.

Lastly, debt is issued in today’s dollars but paid back in future ones, so it gets easier to pay back all on its own over time. Earnings power/wages tend to increase over time with inflation, so $100K today is not the same as $100K tomorrow.

Assuming 3% inflation and corresponding growth in earnings power, a $100K loan, 5 years from now, will feel like a $85,900 loan would today (100,000 x (0.97^5)). Due to inflation, the principal on the loan will get easier to pay back over time all on its own.

In short, borrow money to buy dividend growers because you get the tax-deduction (in Canada), real estate returns with much less leverage, substantially increased diversification versus a rental property, improved liquidity, and the fact debt has a habit of inflating away.

The main point is that borrowing to buy stocks may be more unpopular than it is risky. That’s the sell anyways, we’ll see if it stands the test of time.

Conclusion

To sum up, there are two “common-sense” ways of investing for retirement. First, invest in real estate with mortgages, which gives one the benefit of diversification of meaningful time in the market but comes at the expense of diversification of assets.

The second option is to buy a low-cost index fund with cash savings (usually the S&P 500), which offers the benefit of diversification of assets, at the expense of diversification of time meaningfully exposed to the market.

This article discusses a third strategy, which may be as effective as it is unpopular: borrow to buy equities because it confers the benefits of diversification of time periods and assets; an investor gets the strengths of both commonly accepted investment strategies, without their weaknesses.

I am unsure why more people don’t do this. It may simply be that I’ve missed something important, people who do it don’t discuss it, or real estate has had such a good run people can’t imagine doing anything else. I honestly don’t know. This shouldn’t be a problem, but psychologically it may be.

Borrowing to buy dividend growth stocks certainly passes the rationality test, but brains are not entirely rational, there are a lot of emotions involved. Simply because I don’t know anyone else who does this will make me more scared of doing it, which may lead to behavioural risks.

For example, I may sell when my stocks go down, which I ordinarily wouldn’t do but for the fact the stocks were bought with borrowed money, and that I’d look stupid to others if it didn’t work out. I’d love to say I don’t care what other people think of me, but I do.

Overall, my main takeaway is that borrowing to buy dividend growth stocks is rationally wise but emotionally stupid. As such, I’m going to dip my toe in, start with a small amount of leverage, and see how things progress.

I did the Smith Manoeuvre successfully years ago. It probably took about 1.5-2 years off my mortgage. It is so fascinating the psychology of debt and leverage. How many that invest in real estate make large sums due to the massive leverage. Really enjoy these posts.

Thanks for your thoughts on this. I have thought about it a couple times but have never ended up actually doing it and I am in a 40% plus tax bracket. One point to think about in your calculations is the tax you would pay on the $5,000 of dividends. I have not looked into it recently but then there are also preferred Canadian dividends versus US dividends where you get better tax treatment. So far I have only invested in registered accounts so haven't had to deal with it. Interested to know your thoughts. Thanks again.